By Barbara Fraser

When a slick of oil and dead fish drifted down the Cuninico River in late June 2014, residents of the village of Cuninico could not foresee what a spill from a nearby oil pipeline would mean for their community of some 80 families. Eight years later, the fishery that sustained the villagers hasn’t recovered, health care promised by the government in response to a lawsuit by the affected communities was only partly delivered, and payment for damages is still pending.

“Things are difficult,” said César Mozombite, a leader of the community of Cuninico, on the riverbank where the narrow Cuninico joins the Marañón River in Peru’s northeastern Loreto region. “There’s a scarcity of food. We lost the fish. Many fathers and young people are leaving the community to work to support their families. Life is hard here now.”

For people living in Peru’s Amazonian oil fields, spills from wells and pipelines have been followed by a cascade of consequences. Some, like tarry residue and discarded equipment, are visible. Others, like economic upheaval, are less obvious at first glance. And there is persistent uncertainty about the long-term impacts of oil spills on the environment and human health, as well as about how — or whether — the environmental damage will be cleaned up.

Compared to some of the world’s most infamous oil spills, like the Exxon Valdez in the United States or the Prestige off the coast of Spain, the one upstream from the Kukama Indigenous village of Cuninico was small — some 2,300 barrels of oil leaked into the canal that’s meant to keep spills contained. But in this part of the world, where most villagers rely on surface water for drinking, cooking and bathing and have no way of removing industrial contaminants, even a small spill is disastrous.

In Cuninico, the oil spill triggered a series of impacts, some of which were evident immediately — like the oil-soaked fish, birds and vegetation — and others that crept in over the subsequent weeks and months.

Although they lived near what had been some of the area’s richest fishing grounds, overnight the villagers lost both their main source of protein and their livelihood, as traders shunned their fish. People were afraid to draw water from the river, which had been their primary source, and mothers worried about their families’ health. Eight years later, those fears persist.

In the government, the events marked a change in the way the state-owned oil company Petroperú, which operates the pipeline, handled spills. Immediately after the oil slick was discovered, the company hired men from the community to find the rupture in the pipeline, which by then was under more than three feet of water and thick oil. The men immersed themselves in the oily water as they sought the break, wearing ordinary clothes as they were given no protective gear.

A report broadcast by Channel 5, a Lima-based television channel with a nationwide reach, which also revealed that several minors were among the laborers, forced the replacement of Petroperú’s entire board of directors. The company also began working with contractors who were required to provide protective equipment to workers.

The cleanup created jobs that paid the equivalent of around $25 a day, more than seven times the usual local rate for day labor. The pay, which was a magnet for outsiders seeking work, also set off a round of inflation. Flor de María Parana, Cuninico’s “Indigenous mother,” or women’s representative, said the price of eggs rose from five for one Peruvian sol, equivalent to about 30 cents, to two for a sol, and then a sol a piece. Even after the cleanup work ended and the jobs went away, prices never quite returned to their pre-spill levels.

Leaders of Cuninico and three other communities that had fished in the same area filed lawsuits demanding health care and indemnification for lost livelihoods and environmental damage. They argued their case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, where Parana brandished a bottle filled with oily water at representatives of the Peruvian government and state-owned Petroperú. So far, however, promises of aid have gone largely unfulfilled.

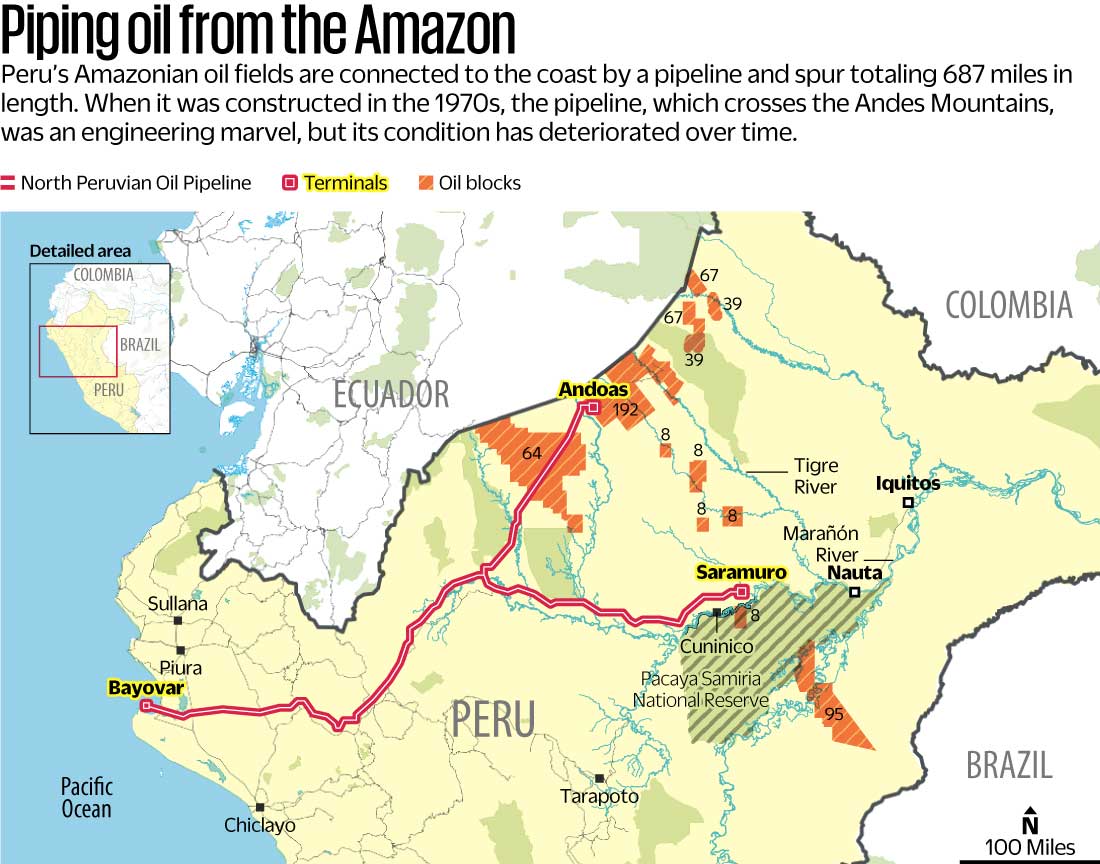

Despite the cleanup, oil remains in the sediment under the pipeline. The same is true in other communities in the Marañón River watershed that have suffered spills from the Northern Peruvian Pipeline, which runs through Cuninico and dozens of other communities along its route to the coast, or from pipelines in Lots 192 and 8, the oldest and largest oil fields in Peru’s Loreto region.

Oil remains in sediment

Heavy seasonal rains cause rivers to overflow their banks for months at a time, depositing crucial nutrient-bearing sediments in the forests, but also washing contaminants through Loreto’s vast, biodiverse and hydrologically complex wetlands, where villagers depend on the rivers and forests for sustenance.

The rainy season in Loreto runs roughly from November through May, and by early April this year water had risen past the first floor of the several dozen wood frame houses in Nueva Unión, an Urarina village on the Chambira River, a tributary of the Marañón. As the river rose, families had gathered their possessions and moved to the second floors of their tin-roofed homes.

At the back of each house, the kitchen platform, with a square, sand-filled pit for the traditional three-log fire, remained above the water level, as ducks paddled beneath the floorboards and chickens roosted in coops built on stilts.

“ In 40 years of oil production,

there’s been no development

for the Indigenous people

of the Chambira ”

Gilberto Inuma Arahuata

Until the water level dropped again, all outdoor activity — from visiting neighbors to going to school — would be done by canoe. In front of most houses, a small floating platform of logs lashed together doubled as a boat dock and place for washing clothes and bathing. Children splashed in the water in the heat of the day, while older kids played a sort of water polo around half submerged soccer goal posts beside the wooden elementary school.

In the middle of the community, two aging pipelines rose from the flooded forest then disappeared under the river, emerging again beside a control cabin on the far bank. The pipeline carries crude oil from oil wells upstream to Petroperú’s pumping station No. 1 at the town of Saramuro, on the Marañón River. On a sunny afternoon, someone had hung a freshly washed blanket over one of the pipes to dry.

Not far from the community, along the pipeline route, an oil spill nearly a decade ago was inadequately cleaned up, community members say. The spot is under water at this time of year, but community leaders have photos from the dry season that show crude mixed with the soil.

Residents of Nueva Unión and Nuevo Perú, slightly downriver, worry about what happens to that polluted sediment when the rains come and the river rises. Children and adults suffer from stomach pains and diarrhea, but it’s hard to tell whether that is caused by industrial contaminants or coliforms that may drift out of flooded latrines, or whether it’s a combination of the two. Peru’s water quality standards for Amazonian rivers do not take into account the number of people throughout the region for whom the waterways are the only source of drinking water.

As in the other watersheds throughout the Amazonian oil fields, the revenue from 50 years of oil production has not been invested in the construction of permanent potable water or sanitation systems in the communities closest to the pollution.

As part of an agreement with the government, temporary water-treatment plants were installed in 2014 and 2015 in about 60 communities, but virtually all of the other communities along the rivers are drinking water from sources that are unfit for human consumption.

The plants were meant as a stopgap while permanent potable water systems were built, but those systems have yet to materialize. In communities that do have plants, parents say diarrheal diseases have decreased, but in larger communities, families living at a distance from the plant still resort to polluted surface water.

None of the communities in the lower part of the Chambira River received water treatment plants, so families in Nuevo Perú and Nueva Unión draw water from around their flooded houses.

“We’ve been suffering from the pollution for many years,” said Gilberto Inuma Arahuata, the 33-year-old president of the Federation of the Urarina Indigenous People of the Chambira River (FEPIURCHA, for its Spanish initials), who lives in Nueva Unión. “The water, soil and air are contaminated,” he added, and because people depend on crops and fish, “the food we get is contaminated, too.”

Food, drinking water scarce in rainy season

During flood season, the lack of safe drinking water combines with other difficulties. In recent years, both Nueva Unión and Nuevo Perú relocated to the bank of the Chambira River from more distant tributaries, which were less accessible, but also less likely to be affected by industrial pollution from upstream.

Although leaders of both communities say the decision was made by the villagers, researchers who have done extensive interviews in the lower Chambira say older residents were reluctant to relocate and that outsiders encouraged the communities to move so they could be reached more easily by government assistance programs, as well as by possible future development projects.

Where they were before, the communities had higher ground for staple crops like corn, cassava and bananas. In their current locations, everything is underwater during the rainy season. They also had easier access to the palm swamps called aguajales, where women collect shoots of the aguaje palm (Mauritia flexuosa), which they use to weave textiles that recently have been recognized officially for their cultural significance.

Some families maintain small plots of crops in the community’s former location, three or four hours away in a canoe known as peque-peque for the chugging sound made by its small motor. But when the floodwaters rise, the villagers’ diet becomes more precarious.

“Access to garden plots took back seat to promises of projects and improvements,” said anthropologist Emanuele Fabiano of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru in Lima, who was working among the Urarina communities in the lower Chambira when they decided to move.

Discussion of the relocation was so intense that he was surprised at the decision.

“People saw it as an opportunity that shouldn’t be missed,” he said, “even though everyone realizes that [in the new location] there are no garden plots and the quality of water is not good.”

The move to the Chambira also provided easier access to goods sold by traders who travel from village to village along the river. As a result, more processed foods have gradually crept into the villagers’ diets, Fabiano said.

That shift was accelerated as people got temporary jobs with the oil company, cleaning up spills or doing other maintenance along the pipelines. In communities where cash income was almost unknown until a decade or so ago, people suddenly had a laborer’s wage, at least from time to time.

‘The Chambira is forgotten’

For Inuma of FEPIURCHA, however, the benefits have been uneven. Pluspetrol has negotiated damages and pipeline right-of-way payments, but the deals have been struck community by community, with settlements depending more on the leaders’ ability to bargain than on consistent criteria, he said.

“In 40 years of oil production, there’s been no development for the Indigenous people of the Chambira” he said. “The ones who’ve gotten rich are the cities.”

Narrow and winding, without any regular public boat transport, the Chambira is one of the most inaccessible watersheds in the oil fields. Because of the distance and the difficulty of travel, the Urarina people living there have had less contact with communities along the Marañón or the cities of Nauta and Iquitos. Women dress in a distinctive style, with bright blouses and darker skirts, and the Urarina language is spoken more than Spanish.

Like other Urarina communities, Nueva Unión lacks basic services like water and sanitation, and the wood frame school has only basic furniture, without even dividers to separate the different grades. Last year, however, some families obtained small solar panels through a government program, so a number of houses now sport a light bulb or two at night and people can charge cell phones, although the signal is unreliable.

About half an hour upriver by peque-peque, the village of Nuevo Progreso is larger and somewhat more commercial. A mix of Urarina and mestizo families, the community’s population swelled when people arrived to work on the cleanup of an oil spill in a lake along the pipeline route.

The community has some tanks for collecting rainwater, but many people still depend on surface water. Nuevo Progreso also suffers from other problems similar to those of Nueva Unión and Nuevo Perú downstream, including a lack of steady jobs.

Health care is also inadequate — for anything requiring more than basic care, people must travel downstream to the Marañón. Schools have only the most basic materials, and during the rainy season parents worry about their children’s safety going to and from school in canoes. Making matters worse this year, several weeks after classes had started one elementary school teacher in Nueva Unión and three high school teachers in Nuevo Progreso had still not shown up for work.

“The Chambira is forgotten,” said Hermógenes Tuanama Canayo, the lieutenant governor of Nuevo Progreso. Oil revenue and other budget funds haven’t trickled down to the riverside communities, he said, adding that politicians “have to see how people live here.”

Water quality remains a constant concern. In a palm swamp at the edge of the lake where the oil spill occurred near Nuevo Progreso, the upper fronds of aguaje trees are dying back, possibly because of oil that has soaked into the soil. Tuanama said some of the residue from the cleanup was dumped into that swamp.

“The Chambira is forgotten”

Hermógenes Tuanama Canayo

Wading into the waist-deep water in early August, he pulled a sack full of oil-soaked soil out of the swamp. As he probed around his feet with a stick, an oily slick appeared and floated across the surface of the water.

Like the residents of Cuninico, on the Marañón River, and other communities close to and downstream from oil operations, he and others along the Chambira blame the pollution for a decline in fishing over the years. They say they must travel farther from their villages and set more nets, and even so they catch fewer fish — and those they do catch are “big-headed,” with skinny bodies.

Although some of the decline is probably due to overfishing, as commercial fisheries have expanded to feed growing urban populations, scientists say oil pollution also takes a toll on fish.

‘We want change in the Chambira’

An oil spill kills some fish immediately, but there are also long-term effects, said Valter Azevedo-Santos, an ichthyologist at Brazil’s São Paulo State University who led a recently published study of the impact of oil and mining on fish in the Amazon. Some components of the oil can affect a fish’s vision, heart and ability to swim, making it difficult for them to hunt prey or find other food. That could be one reason why people say fish are skinnier, Azevedo-Santos said.

Other substances, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can cause cancer and mutations and affect fish embryos and reproduction. Metals like mercury in the produced water that was discharged from oil wells into rivers and streams for decades can accumulate in fish muscle tissue and livers.

“If the oil remains in the environment, especially in the sediment, it can disrupt the ecosystems for years,” Azevedo-Santos said. Those impacts can ripple through the food web, he added, affecting animals and birds that feed on fish, as well as people who catch them.

Disruptions to fisheries have an economic impact, as families in Cuninico learned after the oil spill there. In Indigenous communities in polluted areas, a scarcity of fish may also mean that children do not learn the fishing skills that are an important part of their people’s cultural identity, Azevedo-Santos said.

He advises ongoing monitoring along pipelines and at spill sites, but there are no long-term studies of the impacts of pollutants on fish or other wildlife or on the ecosystems in Peru’s Amazonian oil fields. And Peru has no regulations setting maximum allowable limits for metals or hydrocarbons in sediments.

Nor is there long-term monitoring of the impacts of pollutants on human health. Concern over possible health impacts has increased since 2006, when Peru’s Ministry of Health issued a report showing high levels of cadmium and lead in the blood of residents of Achuar communities along the Corrientes River. Lead affects the neurological system, especially in children, while cadmium is a carcinogen and can cause kidney disease and gastrointestinal problems.

Subsequent testing in other communities has shown high levels of some metals in residents’ blood, but there have been no ongoing environmental health studies to determine the sources of the metals and — more crucially — how to reduce people’s exposure to them.

Meanwhile, the water rises and falls, year after year, stirring up contaminants, and most residents of rural communities continue to lack basic water and sanitation services, access to health care and decent schools. A government plan to “close the gaps” in services to communities in the oil fields has made little progress.

In Loreto, some people are beginning to talk about a “post-oil” future, but communities in the oil fields still await access to basic rights.

“We want a change in the Chambira,” said FEPIURCHA’s Inuma. “After so many years of damage and death, we want development in the Chambira. We want basic services — schools, health care, water, sewers.” And in polluted areas, he adds, “We want remediation.”