By Barbara Fraser and Marilez Tello

Lindaura Cariajano Chuje scrambled up the riverbank and strode into the forest, following a path only she could see. A step ahead of her, a young man with a machete cleared the way as she gave instructions: A little to the left, a bit to the right, now straight ahead. It was a muggy morning in September 2018, and the only sounds were the rhythmic buzz of cicadas and the muffled sound of the machete.

A few minutes later, there was a subtle change in the soft soil underfoot as the ground became uneven, with very slight depressions. Cariajano paused, resting her hand on a slim round wooden marker that was nearly invisible amid the tropical foliage.

“This is my first daughter,” she said.

Cariajano had been a young mother when the stream that provided water and fish for her and the other residents of Vista Alegre, a Kichwa Indigenous community along the Tigre River in northeastern Peru, turned black. Somewhere upstream, a well or a pipe in one of Peru’s newest oil fields had leaked into the surrounding forest and waterways, and the crude had washed downstream.

Not long afterward, people in the village began to fall ill with stomach cramps. Many died, writhing in pain and vomiting blood. Among them was Cariajano’s first child, 6-month-old Lisette. But she was not alone. Waving her arm in an arc, Cariajano gestured at the overgrown cemetery. “All of the children are here,” she said.

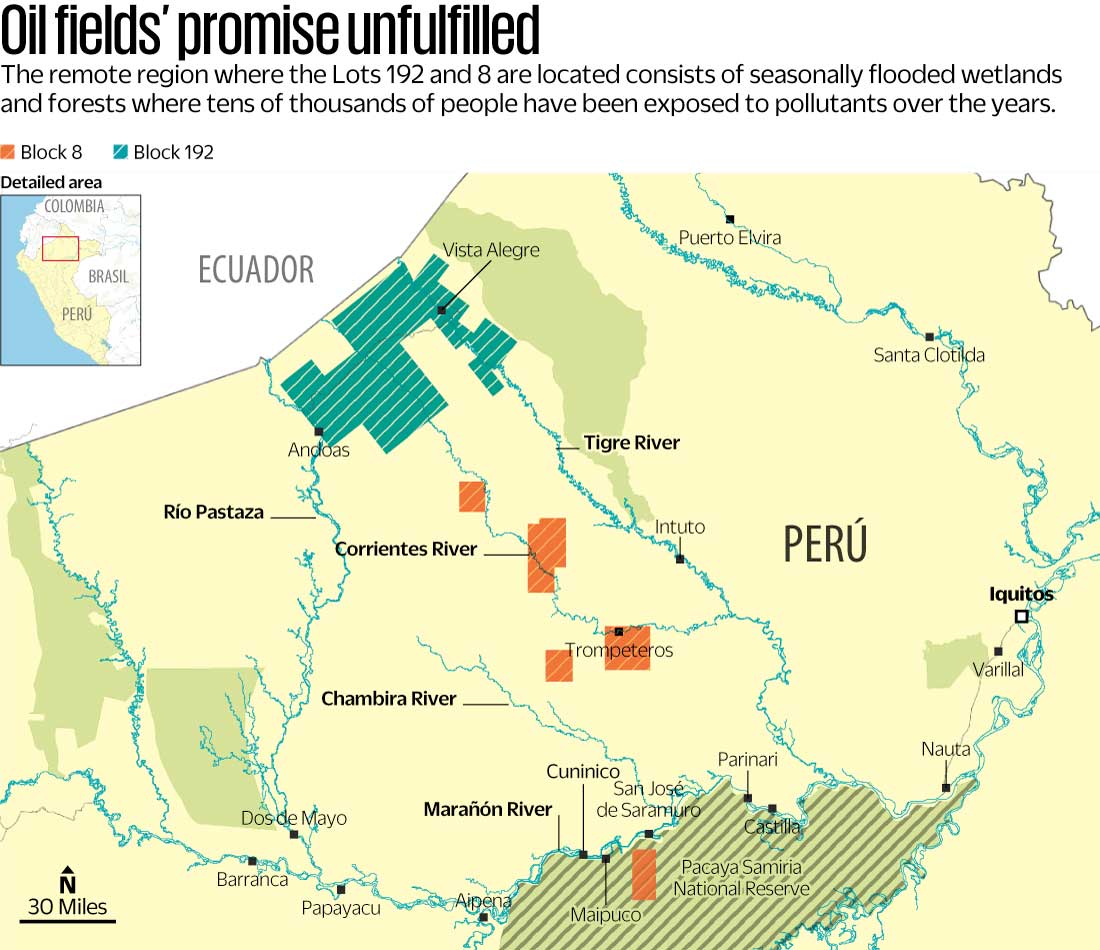

The Tigre River winds through Peru’s largest oil field, known now as Block 192, in a region inhabited largely by Indigenous Quechua, Achuar, Kichwa, Kukama and Urarina people. When prospectors struck oil there in 1971, government officials promised that the industry would bring development to a region that had languished since the rubber boom went bust half a century earlier.

But 50 years of oil production have left deep wounds in the communities and in the land. Poorly regulated companies cleared forests to make way for oil wells and a network of pipelines connecting them to storage facilities in the region and on the coast, more than 500 miles away. Oil spills were ignored, while produced water —the hot, salty, metals-laden water pumped out of the wells with the oil — was dumped into streams or onto the ground.

In this remote corner of Peru, where there still are no roads except the ones built to service the oil wells, most people still drink untreated water from rivers or streams. When the river turned black or the water tasted salty, those who could dug wells or hiked to cleaner tributaries. Those who had no choice pushed the oily slick aside and drew water that looked clean, without knowing it still contained hydrocarbons, heavy metals and other toxics.

By the time Peru began implementing stronger environmental legislation in the 1990s, irreversible damage had already been done. As villagers came to understand the hazard posed by toxic waste from the oil operations, they began to organize to demand safe water, health care, cleanup of polluted sites and restoration of poisoned ecosystems. By then, however, their relationship with the oil companies was complicated, as the industry that provided jobs and some other benefits was the same one that had contaminated their land, waterways, fish and game and caused still-unknown harm to their health.

As the industry declines, with the oil fields playing out and climate change pushing the world away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy, the communities in Peru’s Amazonian oil fields still lack safe drinking water, sanitation systems, electricity and decent health care and schools. With the war in Ukraine sending oil prices to record levels, government officials are trying to breathe new life into the industry. And although a recent study of Block 1AB, as 192 was originally known, and another of nearby Block 8 have laid the groundwork for future remediation of polluted sites, that work — if actually carried out — would take decades and billions of dollars.

But despite the uncertain future, time will not erase the memory of an industry that has left a lasting imprint on the region and its people.

First signs of change

Eight-year-old Lindaura Cariajano and other children were swimming when they heard strangers approaching through the forest. They fled in panic, leaving even their clothes behind. The men told them, “We’re clearing trails. We’re looking for petroleum.,” she recalled. “My friend asked me, ‘What’s petroleum?’”

Shortly afterward, more gringos arrived in a helicopter — the first time villagers had seen such a machine. Georgina Vargas, a midwife in Vista Alegre, recalled taking refuge in her house, where she hid in a pile of clothes. But her husband, who had once lived far downstream, on the lower Amazon River, was unperturbed. He told her not to be afraid and he allowed the intruders to camp in their garden.

Cariajano remembered the adults meeting and deciding to allow the men to build their work camp at the edge of the community. The workers offered children treats like crackers and jam — items they’d never seen before — or gave them food that was left over after meals. Cariajano’s mother warned her children not to eat the strange food, saying it was poisoned, and there were rumors that the outsiders were pelacaras, creatures that would strip the skin from a person’s face and suck out their body fat, which in the Amazon are often associated with fair-skinned outsiders.

As disturbing as they were, those initial encounters offered barely a hint of the drastic changes that would sweep rapidly across the fairly isolated region that included the Pastaza, Corrientes, Tigre, Chambira and Marañón watersheds, as thousands of workers flocked to develop what would become two of Peru’s most productive oil fields.

First came the trocheros, who cleared the paths, or trochas, for seismic exploration. The villagers heard explosions and felt the vibrations as the workers drilled holes and set off charges at 300-foot intervals along the paths, creating shock waves that allowed engineers to map the oil deposits.

The men spent weeks at a time hacking paths several meters wide or more through the dense tropical vegetation, and clearing larger areas at intervals to allow helicopters to land. They were accompanied by “deafening machinery, consisting of portable drills, electricity generators, air compressors, chainsaws, outboard motors, land vehicles and helicopters, a constant racket,” indigenous rights lawyer Lily la Torre wrote in her book, All We Want is to Live in Peace.

Entire villages were displaced to make way for worker camps, and the trocheros laying the seismic lines sometimes cut straight through a community. Over the next two decades, more than 6,200 miles of seismic lines were cleared in the oil field known first as Block 1AB and later as Block 192, which was in the hands of Occidental Petroleum, and more than 3,000 miles in neighboring Block 8 and 8X, operated by state-owned Petroperú.

Debt labor and toxic rivers

The disruption brought a cascade of changes to the Quechua, Achuar, Kichwa, Kukama and Urarina villages along the rivers, according to Ecuadorian anthropologist María Antonieta Guzmán-González, who has studied the impacts of the oil industry, especially in the upper part of the Tigre River.

“The arrival of the oil company meant the arrival of many people — many workers, but also merchants, who arrived and settled in the area, as well as traders,” she said.

Traders and loggers had already visited those watersheds, but with the arrival of the companies exploring for oil, those activities intensified, she added.

Initially, the companies did not hire Indigenous people as laborers, but traders paid villagers to provide game meat and other products, under a debt-labor system that had existed at least since the rubber boom that swept the western Amazon earlier in the 20th century.

The trader would equip the hunter with supplies, which would be discounted from his payment when he delivered the agreed-upon goods. With the trader’s thumb on the scale, however, the hunter often ended up with an infinite debt. The combination of noise from boats, helicopters, construction and seismic charges, along with clearing forest for camps and new villages to accommodate the influx of settlers, caused game animals to flee from areas that had traditionally been communities’ hunting grounds.

Hunting and fishing to feed so many people also depleted wildlife populations, while loggers arrived along with the companies, taking advantage of the opportunity to cut and sell trees like mahogany and cedar, skimming the forest of the large, slow-growing trees that produced the most valuable timber.

Throughout the Amazon Basin, life centers around rivers. In many villages, houses are arranged in a row along the river bank, and although there are no fences, it is understood that the area in front of each house is the family’s port — the place where they tie up their canoe and carry out daily tasks.

The day often begins early with children fetching buckets of water for cooking and ends with the family bathing in the river when the day’s work is done. In between, women wash clothes, clean fish and bathe babies on small log rafts. People fish in nearby lakes, and children play in the water in the heat of the day. In most communities, rivers and streams are the only source of water for drinking and cooking.

Aging oil fields, toxic waste

An oil spill in 2014 in the Kukama Indigenous community of Cuninico, on the Marañón River, as well as more than a dozen others

since then, came from the Northern Peruvian Pipeline…![]()

But when the drilling started in the oil fields, the rivers became toxic.

“Before the company came, the river was clean,” Vargas said. But she recalls a late afternoon when she went to the river to bathe after spending the day tending her crops in the tropical heat.

“I felt that my body was sticky,” she said. She touched her tongue to her skin. “My body had salt all over it. My hair was all salty.” She found a stream with clear water where she could bathe to wash the salt away, and she and her husband realized they should stop drinking water from the river. Some people dug wells. But for those who had no streams close by, the rivers were the only option.

Decades of pollution

A 687-mile pipeline — an expensive engineering marvel in its day, which has deteriorated over time — was eventually built to carry crude from the northern oil fields over the Andes Mountains to the port of Bayovar on the Pacific Coast, including a spur from the village of Nuevo Andoas, on the Pastaza River. Until the network of pipelines in the oil fields was completed, however, the oil was shipped downriver by barge.

“That crude that the barges carried sometimes spilled — that much spilled,” Lindaura Cariajano said, holding her hands about a foot apart. “The river was black. The herons were covered with oil. They couldn’t fly, so they died. The fish jumped and landed on top of the oil.” No one had explained to villagers that crude oil and its byproducts were toxic, so people gathered up the fish and sometimes collected oil in containers, inserting a wick to make a small lamp.

Two decades would pass before Peru began implementing environmental legislation, and yet another before the companies operating Blocks 192 and 8 would begin to reinject produced water back underground instead of dumping it into the environment. Meanwhile, billions of barrels of salty, contaminated water were pumped into the rivers and streams. In 2008 alone, an average of 363,000 barrels of produced water were discharged into the environment each day in Block 8 and an average of 576,000 a day in Block 1AB/192. Damage from oil spills has also persisted, sometimes long after any visible oil has washed away.

If rivers and streams are vital for everyday life, it’s the cochas, or lakes, in Amazonian Peru that provide sustenance for villagers. As the rivers rise during the rainy season, water is pushed up streams and through low-lying forest into the cochas, which serve as fish nurseries. Migrating fish, such as the boquichico (Prochilodus nigricans), palometa (Mylossoma duriventre) and doncella (Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum) take advantage of the abundant food supply in the flooded forest, then return to the river as the rainy season passes and the waters recede.

But this ebb and flow, which spreads nutrient-laden sediment throughout the forest, can also stir up contaminants from oil spills that were never cleaned up.

On the day Lindaura Cariajano returned to her daughter’s grave in the overgrown cemetery, Llerson Fachín, the young apu or leader of Vista Alegre, stood on dried and cracked soil around the Cocha Montano. Once a key fishing ground for his community, the lake is now just a fraction of its former size.

“This lake has a very sad history,” he said. “Since the 1980s, after a spill, the lake has been drying up. We’re losing our lakes, which are very important for us.”

Villagers recall the day the water in the Cocha Montano turned black from a spill at a well upstream. Oil covered the lake and flowed out of it and into the Tigre River.

“A lot of fish died here. The surface was black, completely black, and the fish were floating,” Fachín said, adding that contaminants from the area around the oil well still wash downstream into the lake when it rains. None of the companies that have operated in the oil field has ever cleaned it up.

“Nothing has been remediated. Nature alone has cleaned it up — the water, the rain, that’s what has done the cleanup. As the water rose and fell, it got [the oil] out little by little,” he said.

Of the oil operations, he added, “Having those things has meant nothing more than death — death and the loss of our natural forest resources and wildlife, and many human lives that we’ve also lost. I can’t call this progress.”

Mourning deaths of lakes and children

But the death of Cocha Montano goes beyond the environmental devastation. It also marks the breakdown of the relationship between the Kichwa villagers and the natural world with which their lives are inextricably intertwined, in which the forests, rivers, fish, animals and all living things have madres, literally “mothers” — spirits that nurture and care for them, and who will leave the humans bereft if they are mistreated.

“Every stream, every lake, has its madre,” said Julia Chuje Ruíz, Cariajano’s older cousin. “Some are anacondas, some are caimans, some are rays, some are like zúngaro catfish, but big ones. Some are jaguars. Every place has its madre. The river, too — every pool in the river has its madre. But when the [pollution] comes, the madre has to leave. Either she dies or she leaves. Who knows where she goes? And the lake dries up. That’s what happened to Montano.”

When the oily slick washed downstream, blackening the lake and spilling out into the Tigre River, “a giant caiman died there. A huge caiman left the lake. It passed by here, above Vista Alegre,” Julia Chuje said, gesturing into the distance. “There’s a pool in the river there. A huge caiman crossed there. It left the cocha, and maybe it died.”

And the lake dried up.

“Montano is a big stream, and it has smaller tributaries,” she added. “They also dried up. Because their madre left. Their madre died. Who’s going to take care of them? They’ve died, too. The cocha dried up. The stream dried up. There’s nothing left.”

Julia Chuje was 13 when the first oil workers arrived in Vista Alegre, clearing seismic lines that would change her life and those of her neighbors in ways they couldn’t imagine. “What did the company come to do?” she asks. “It seems to me that it came to do away with us. So many deaths, and who is going to pay? Who is going to pay for the harm that’s been done?”

No comprehensive investigation was ever done, so no one really knows what killed most of a generation of children in Vista Alegre, along with some of the young recruits in a nearby military post, in a fairly short time. José Alvarez, who now heads the office of biodiversity at Peru’s Ministry of the Environment, stumbled on the cemetery full of small graves in the early 1990s when he worked in the Tigre watershed.

According to experts he consulted at the time, the symptoms were consistent with hepatitis — probably brought to the area by workers in the oil camps, and possibly exacerbated by exposure to contaminants in the environment. The victims were buried on the outskirts of the community cemetery, and the families moved away. Some settled on the other side of the river, a short boat trip away, where Vista Alegre now stands, and some in the nearby community of Remanente or other villages.

Gradually the forest reclaimed the graves, but it cannot erase the memory.

The cemetery “is abandoned, because it’s far to come,” Lindaura Cariajano said, standing among the trees. Besides her infant daughter, she later lost two other children, who are buried not far away.

“My children died vomiting blood,” she said. “I feel sad for my children. Even the tapirs died, drinking water from that stream. That contamination still exists. The government doesn’t care. They’re at peace — they eat, they drink, their children are fine, and we’re screwed here with this contamination.”

She rested her hand on the slim wooden marker.

“This is my first daughter,” she said. “She would be 35 years old now.”

Editor´s note: Lindaura Cariajano Chuje died of skin cancer in 2019.